Self-governing…again

After about 8,000 years of self-governance, the 150 years under the Indian Act is merely a blip on the radar of the Tla’amin people.

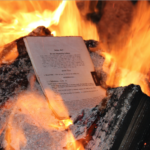

Many gathered around the fire outside Governance House in the early hours of April 5 to burn copies  of that act as a new era began.

of that act as a new era began.

A few days later, hundreds gathered there for the unveiling of six new poles and then the crowd travelled into nearby Powell River for hours of speeches, gift giving and celebrations.

The Tla’amin Treaty marked the largest transfer of lands in BC history – 8,323 hectares including 1,917 hectares of the former Sliammon Indian reserve and 6,405 hectares of provincial Crown land.

The agreement with Canada and BC, more than 20 years in the making, also saw a capital transfer of $33.9 million and an economic development fund of $7.9 million for the nation.

Poles were the stars

When six poles were unveiled on April 9, they marked not only stories-told-incedar beside Governance House, but also a return of almost-lost carving skills to the community.

When six poles were unveiled on April 9, they marked not only stories-told-incedar beside Governance House, but also a return of almost-lost carving skills to the community.

Elder Alvin Wilson never learned to carve as a young man. But of the work, he said: “I’m glad they’re picking this up and passing the tradition on.”

He worked with head carver Darren Joseph from Squamish Nation, Powell River carvers Phil Russell and Ivan Rosypskye, alongside the nation’s Randy Timothy, spokesman for the project, and Vincent Timothy. Working under tight deadlines, the team carved logs donated by Klahoose First Nation from its forestry operations around Toba Inlet.

There are male, female and child welcome poles. Standing behind them are poles representing the past, present and future.

Wilson visioned the ‘past’ pole with a watchman sitting above a bear with a baby and an orca. Joseph designed the ‘present’ pole with ancestors at the top over an eagle, raven and bear. Around the pole are salmon, orca and halibut representing the other carvers.

Students at Brooks and James Thomson schools helped design the ‘future’ pole with a thunderbird ready to fly as well as handprints of several youth.

Clint’s talking stick

Clint Williams now has a new title – he is now known as hegus instead of chief. By his side during the celebrations and ceremonies on April 9 was his talking stick. It was the first time he publicly showed the treasure. “It was given to me by my aunt and uncle – Alvin Wilson and his late wife Lorraine – after my first election as chief,” he said. “It gives me good memories of my grandparents.”

Clint Williams now has a new title – he is now known as hegus instead of chief. By his side during the celebrations and ceremonies on April 9 was his talking stick. It was the first time he publicly showed the treasure. “It was given to me by my aunt and uncle – Alvin Wilson and his late wife Lorraine – after my first election as chief,” he said. “It gives me good memories of my grandparents.”

Scout’s Honour

Scouts Canada’s has given Tla’amin a gift of 74 acres of land. The Scouts had owned the land, southeast of Lund, since 1974. Three other lots that were part of the treaty settlement surround the landlocked parcel.

The Tribal Council

More than one speaker referred to the old Alliance Tribal Council, the forerunner of Naut’sa mawt Tribal Council, publishers of this magazine. “Chief Joe Mitchell (of Sliammon) made the Alliance Tribal Council the genesis of the self-government quest,” said Howard E. Grant – qiyəplenəxʷ– from Musqueam First Nation. He is executive director of the First Nations Summit. Eugene Louie, former Sliammon chief agreed. “The Alliance led the way, way back when.”