qaymɩxʷqɛnəm: the comeback of ʔayʔaǰuθəm at Tla’amin

By Cara McKenna

qaymɩxʷqɛnəm is a word in Tla’amin First Nation’s traditional language that means “to speak in the native language.”

And that’s exactly what people are doing more and more of at Tla’amin, as revitalization efforts – and excitement to learn the ʔayʔaǰuθəm language – ramp up in the community.

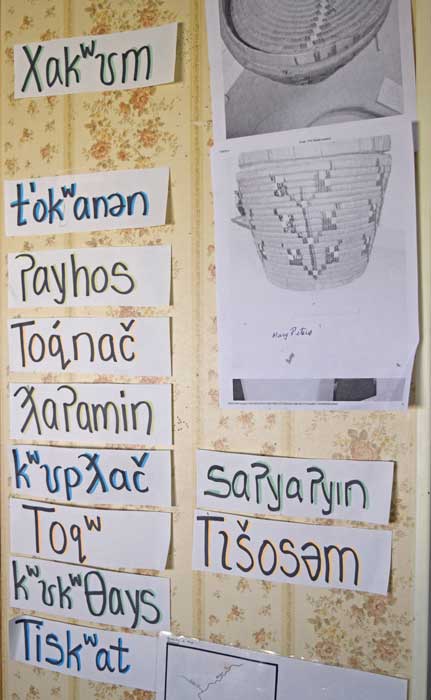

A weekly language club is now in the middle of creating a traditional place names map with the Powell River Historical Museum and Archives after receiving a federal grant to fund the project.

The group is also working on a dictionary, building on thousands of words and phrases that were previously recorded with the Indigenous language resource FirstVoices.

Elder Betty Wilson, a retired school teacher who has been working on language revitalization for several decades, said the projects will be in print and digital formats, so people can hear recordings of words as well as reading them.

“We’re working under the premise that it takes 20,000 words and phrases to save a language,” she said. “With FirstVoices we have 3,000. We’re working on about 4,000 that need to be edited.”

The language club, consisting of community members of all ages as well as academics, meets weekly to record words and plan for the future.

The language club, consisting of community members of all ages as well as academics, meets weekly to record words and plan for the future.

During one of their meetings in July, the group was gathered at Wilson’s kitchen table discussing research and making plans.

“It’s just a matter of our community pulling together,” Wilson explained. “We decided to work with our oldest elders first, because they’re the most fragile, in their 80s. Their knowledge base is more, they’ve experienced the language, they’ve experienced these territories. So that was our goal.”

Tla’amin also has an agreement with the communities who share the language —Klahoose, Homalco and Comox—to work together on revitalization.

“The young people are really interested,” Wilson said. “I always say that knowing who you are gives you that confidence to move forward.”

Devin Pielle, a member of the group who’s been learning the language in classes since Kindergarten, said the community is “fanning a flame” to bring ʔayʔaǰuθəm back.

“It only took three generations for us to get here,” Pielle said. “My great-grandparents were so fluent, they were our first resource people, then you have my granny’s generation which was fluent, they lived the language. But then there’s the block of residential school.”

Wilson did not attend residential school, which allowed her to retain much of the language, but elder Randy Timothy is a survivor of the schools and has been relearning words and phrases.

“I went to residential, but I retained about 30 per cent,” he said. “By being out in our areas, different bays and that, that’s given me a little headstart on some of our youngsters. They need to go out there and discover their land.”

One of those young people, Drew Blaney, said he feels lucky that he grew up hearing the language in his family and through songs.

“I was fortunate enough that my mom took me to this exact spot when I was young and all the elders were speaking the language back and forth,” he said.

Blaney laughed, adding that sometimes that speaking was just to tease the young people.

“But it was still listening to the language and learning it,” he said. “I just really hope when I’m older, I’ll have somebody to talk to.”

Recently, Blaney’s young nephew has been learning and speaking certain words. The nation has had success teaching the language through songs, and a potential immersion program is in the works at the daycare.

Pielle acknowledged the difficulties to passing on the language to the next generations – such as in her family, her husband is Squamish, so there are two languages to think about teaching their daughter.

The language classes at the local high school are also in competition with other classes such as outdoor ed. Then there’s the fact that most families still wake up speaking English.

Also, there’s the issue of finding and applying for funding, and the tendency for language efforts between communities and organizations to be disconnected.

“There are still challenges, but I think it’s pretty fair to say that the excitement about learning the language is there,” Pielle said. “It’s a new time that we can be proud of who we are and where we come from. Where my dad’s generation had to fight to be proud of who they are and where they come from.”

The place names atlas is expected to be completed by the spring of 2018, while the dictionary is set to be completed in about two years.

A few words in ʔayʔaǰuθəm:

čɛčɛhaθɛč – I thank (honor) you

č̓ik̓ saplɛn – frybread

ganaxʷmot – the truth

ǰenxʷ – fish

χaƛʊxʷəs – to love

qaymɩxʷqɛnəm – to speak in the native language

mamaɬaqɛnəm – to speak in the white man’s language

(Source: FirstVoices)