Walking through ‘Unbelievable’ exhibit

By Cara McKenna

“Why do we assume some stories are true when they actually aren’t?” questions Sharon Fortney, a curator at the Museum of Vancouver.

Fortney, who is Klahoose and German, worked on the museum’s latest exhibit titled Unbelievable.

In an age of “fake news” and “alternative facts,” Unbelievable is meant to challenge people’s preconceptions about Vancouver’s history, including the complicated— and often incorrect—narrative that exists around Indigenous people.

It includes many Indigenous pieces that were chosen from the museum collection by Fortney to deconstruct how we know the city and the stories that have been silenced.

The Sentinel walked through the new exhibit with Fortney to learn more about some of those works. Unbelievable is showing until Sept. 24.

THUNDERBIRD TOTEM

“A lot of the things that have become symbols of Vancouver were imported symbols. So we kind of explore that in the exhibit, looking at the Charlie James houseposts in Stanley Park. They became this iconic totem pole that showed up on tourist brochures, postcards, stamps, the city coat of arms. It’s become very pervasive as a symbol of the city but it’s actually imported, and the presence of totem poles, in many ways, silenced Coast Salish architecture in the city.

This housepost is really interesting because it was commissioned for a chief in Alert Bay … before it was purchased by the Vancouver Art, Historical and Scientific Association. They wanted it for a village they were going to build in Stanley Park in the 1920s, and that village was supposed to be an educational village to teach people about the First Nations of the province.

But they were bringing in these northern symbols at the time when the last Coast Salish residents of Stanley Park had just been evicted a few years previously. So there was a little bit of protest, obviously, and the village itself was never constructed, but the totem poles did remain there. There are still totem poles today in Stanley Park.”

QUATCHI AND SQUATCHI

“This was a little bit of playing with appropriation. You’re taking the Coast Salish sasquatch, and you’re making him into a commercial figure to represent the Olympics. And then you’re contrasting him with Squatchi, he was the poverty Olympics mascot. He’s got ‘homes not games’ on his chest. That’s to speak to the fact that a lot of people were evicting their tenants so they could charge high rents for people coming to the Olympics, then there was a ton of money being spent on infrastructure for the Olympics, rather than building affordable housing for the community.”

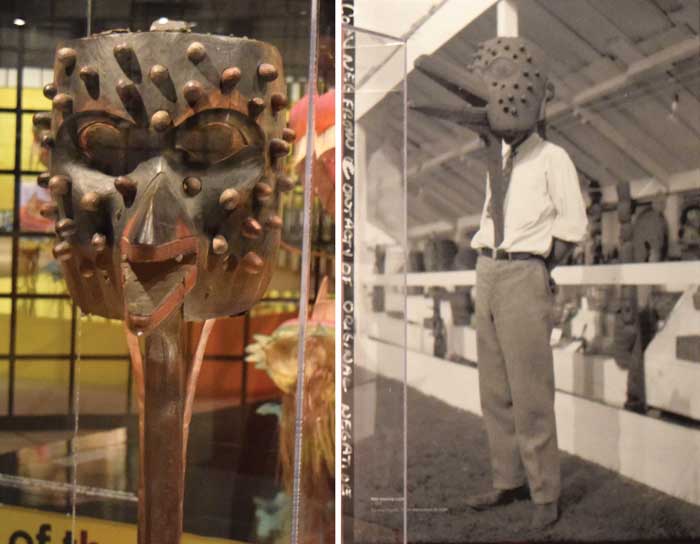

SMALLPOX MASK

“This is a unique older piece in the collection, it’s called the smallpox mask, and we’re not really sure who named it or even how it got into the (museum) collection. But in terms of doing our exhibit, we thought it was a good way to tell a contact story about disease and the impact that newcomers had on First Nations people when they came here. Smallpox and other diseases actually reached the Coast before the first Europeans sailed their ships into Burrard Inlet and up and down the Coast. There already were people who showed evidence of smallpox, and that’s because it spread across train networks across the continent and people had no resistance. So it already had a very devastating effect before the first Europeans even arrived here.

We couldn’t find out much about the history of this mask, and I found these photographs that were at the B.C. provincial museum and they’re actually non-Indigenous people wearing the mask. This organization called the Native Sons of British Columbia. So to be a Native Son you were of a generation that was born here after the first settlers came, but you weren’t actually Indigenous, though they did allow people of mixed ancestry into the organization. They were a bit of a patron organization. They had ownership of this mask in the 1920s and they did their exhibiting every year. I know sometime between around 1923 and 1940, this mask made it into the MoV collection but I can’t even find it in our ledger. So it’s a bit of a mystery. We just don’t really know much about how it got here and as far as I know it’s the only smallpox mask that’s in a museum collection on the Coast (with B.C. origins).”

MANHOLE COVERS

“This is a bit interactive. Here’s a manhole cover by Susan Point and her daughter Kelly (Cannell). You can actually do a rubbing of it if you want, and then they’re contrasting it with the idea of the gridline manhole cover and the idea of the city being mapped and renamed to claim it for other people. So there are different ways of looking at even the architecture in the city and thinking about our past.”

GEORGE RALEY’S PRINTING PRESS

“It’s a miniature printing press that belonged to George Raley. He was a Methodist missionary who worked up in northern B.C. with Tlingit, and then he later ran the Coqualeetza residential school out in Chilliwack, so he inherited a printing press and he printed his own missionary newspaper, it’s called Na-Na-Kwa. His whole goal with his little paper was to send it to eastern Canada and get more funding so that he could continue his missionary work. Sometimes he also published in the Tlingit language which created a record of the language, which is important today when people are working so hard to reclaim language.

What I thought would be interesting as a different perspective or story was to get some coverage from the Native Voice. I thought, let’s look at stories that First Nations people thought were important. Issues that mattered to them. It was a bit of a later paper, we’re looking at the 1890s here and this one we’re looking at the 1940s and 50s, but just the stories are quite different. They’re written and edited, often, by First Nations people and it’s relevant to their lives, like B.C. province giving the vote to Native Canadians in the 1950s. I don’t think a lot of people realize that First Nations didn’t have the vote, that they were treated like children under the Indian Act.”

SOUVENIR AND LEGACY CASE

“On one side there’s souvenir, and on the other side you have legacy. We’re trying to get people to look at these belongings from two different perspectives, with the labels. That’s why they’re kind of turned so you can see them with interest from both sides.

On one side, we tell the souvenir story and look a little bit at why did people collect Native art in the early 20th century and their interest in model totem poles and basketry collections. Then on the other side we look at it from the perspective of Indigenous people and they were living in a time when the Indian Act was really restrictive on what types of cultural traditions that people could practice. When you had a carver like Tommy Moses, who was Squamish, he’s adopted a northern carving style but at the same time he’s able to practice a traditional art form, there may be stories embedded in his carvings, he’s still preserving culture even though it might not have looked like what it looked like in the past century. It’s really a story of survival and persistence as well. Same with the basketry. Some forms of weaving were not allowed at residential school, like wool weaving was not really allowed because it was really linked to ceremonial life. But basketry was allowed and I’ve worked before with elders who, when they were at residential school, were allowed to teach basketry in the bathroom. Because that’s where the water source was and you need water when you’re working with a root. When you talk to people about basketry, a lot of the ways you work with the basketry materials, it’s family-owned knowledge. They were actually able to preserve specialized knowledge from their family while making what the missionaries viewed as handicrafts.

There’s these three wooden pieces, and they’re all made by the same boy from St. George’s Indian Residential School which was up in the valley near Yale, and they all show Coyote on it. In the Interior, Coyote is a transformation figure. They’ve transformed him into a prayer leader. There’s a story on the back of this plaque. He’s been turned into a prayer leader but he’s ascended up into heaven, he’s still got a lot of his supernatural qualities. So even though they’re in a very restrictive environment, they’re creating belongings and objects that still carry traditional elements. So what are they allowed to do in the context of the law, of residential school, and how did people carry this tradition forward? It’s a complex message.”