Digital Mapping

A POWERFUL RIGHTS AND TITLE TOOL

During a four-day Indigenous mapping workshop at the University of Victoria, representatives from over 100 aboriginal organizations shared stories and ideas about using Google technology in their territories. Combining old and new knowledge, First Nation groups are creating territory maps, doing environmental monitoring and charting traditional place names.

Anthropology professor Brian Thom, who co-organized the workshop, said that the maps lend a powerful voice and knowledge set for nations fighting against, or looking at, development.

“These maps are powerful and really become a common language that focuses our minds and gets us thinking about the potential impacts of developments on the exercise of aboriginal title and rights,” he said.

“Part of what’s really exciting is that indigenous communities have been really taking a leadership role in investing in their communities to build, in-house, the capacity to do this research themselves and manage the map data and present it. There’s a real critical mass of First Nations who are leaders in these projects.”

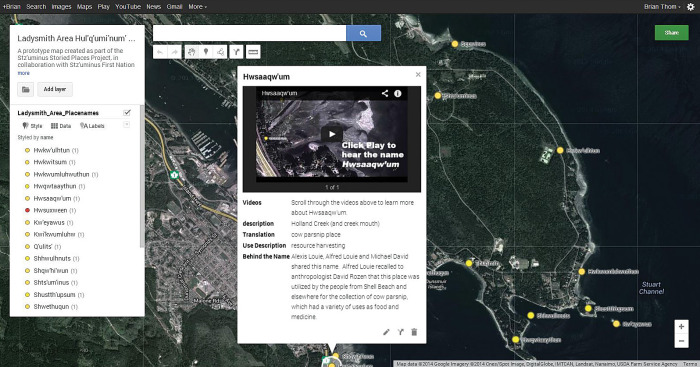

Stz’uminus First Nation, for example, has recently been mapping traditional place names, a project that has allowed elders and youth to collaborate and learn from one other.

“The youth are out talking to the elders about these important places and they live the importance of these areas through mapping,” Thom said.

“These maps are such a powerful way to assert, you know, this is our territory. I think the nations who have made these efforts of documentation will really see the benefit of being able to speak with a powerful voice. I think the other benefit is really the engagement of the youth.”

Pano Skrivanos, the protocol and agreement co-ordinator at Tsleil-Waututh First Nation, added that “knowledge is power.”

First Nations across Canada are looking to Google Earth tools as a way to assert their title and rights, creating what an expert calls a “critical mass”.

Skrivanos worked with a team to compile almost 700 place names within Tsleil-Waututh’s territory and has often been able to use the information when it comes to the nation’s fight against big oil in its territory.

“The more information that you know about a given place, it’s only going to help you,” he said.

“I can use the pipeline as an example. Trans-Mountain wants to twin their existing pipeline, so we did some analysis on the areas that would be impacted by that pipeline and right away you can see (from the maps) that those areas are important.”

Tsleil-Waututh has also mapped historical travel routes, among other projects.

During the UVic conference, Skrivanos was one of many presenters who also did ‘deep dives’ into Google Earth technology with Google engineers to learn specifics of more complicated controls.

Thom said that nations can get involved in mapping by accessing training toolkits through UVic’s ethnographic mapping lab, or by going through consulting firms.

“But there are many nations that have been doing these projects since the mid-‘90s,” he said.

“Some might be in storage somewhere. I would really encourage people to see the value of those old tapes and maps and bring them into computer systems where people can use them.

“Bring them into Google Earth, bring them into the hands of the people who help make decisions. Because this kind of mapping can really empower First Nations governments.”