What does reconciliation mean to you?

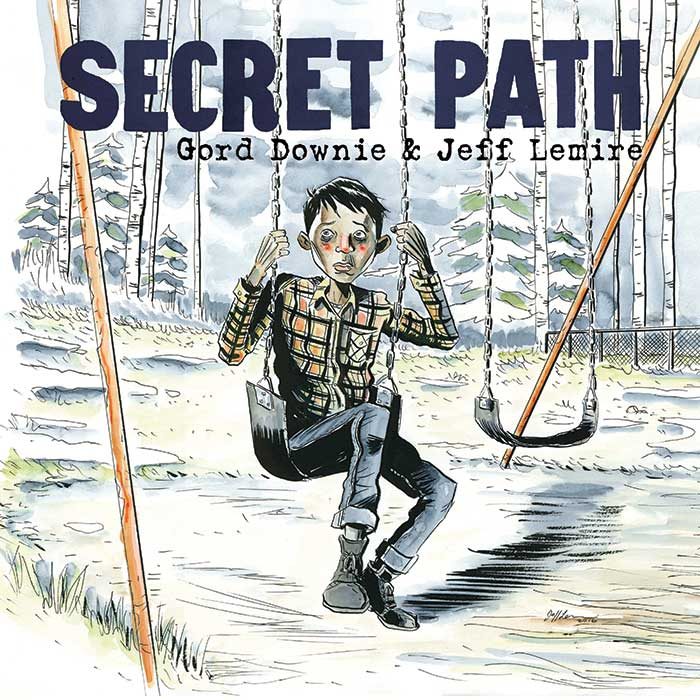

In the last issue of the Sentinel, we featured content from Secret Path, a multimedia project led by Gord Downie, front man of the band Tragically Hip.

It tells the story of 12-year-old Chanie Wenjack, who died in 1966 as a runaway from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario. The project includes a 10-song album by Downie and others as well as a graphic novel by Jeff Lemire that has already become a best seller.

Proceeds from sales of Secret Path go to the Gord Downie Secret Path Fund for Truth and Reconciliation at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at The University of Manitoba.

We also invited readers to answer the question: What does reconciliation mean to me? Top entries will receive a copy of the “Secret Path” book and album download. Readers can still send their submissions to editor@salishseasentinel.ca.

Below are two submissions we’ve already received, one long and one short.

Reconciliation begins in our hearts

By Craig Spence

Like many Canadians, I don’t know what to do about reconciliation. But as a writer I know ‘doing nothing’ constitutes a dereliction of duty.

As I said to a First Nations acquaintance over coffee last week, there are many people of European descent who are as troubled and perplexed as me when it comes to reconciliation: people who acknowledge the devastating assimilation that was perpetrated against aboriginal peoples in North America; and the unchecked occupation and pillaging of indigenous territories and cultures that had been established over thousands of years.

Acknowledging those atrocities is an important first step, but it doesn’t bring us much closer to an understanding of what is expected of us, and what we as individuals can do to help set things right. So I decided to go see Carey Newman’s Witness Blanket on exhibit at Vancouver Island University’s View Gallery in Nanaimo, thinking I might discover something in the 40-foot display of residential school artifacts that would give me insights.

As I studied the fragments of residential school history compiled in the Witness Blanket, I thought, “I did not do this.” And asked, “Why should I apologize?”

It’s natural to look for a way out when we are confronted with something that looks like ‘blame.’ Then it occurred to me that apologizing is about more than accepting blame, it’s also about taking responsibility for the effects of grave social injustices that are still impacting the lives of tens of thousands of Canadians today.

As a nation, we do inherit the blame for our ancestors’ actions, and if we do not apologize in that sense, who will apologize and begin the work of healing?

As importantly, by apologizing, we accept as individuals our responsibility to make right as best we can the wrongs that still weigh heavily on so many people in this land.

Both facets of apology must be made and continue to be sincerely offered for as long as it takes to establish trust and achieve reconciliation.

Apology must be more than words, too; a sincere apology emerges out of genuine soul-searching and personal reform. To apologize in that sense means becoming aware of our own prejudices, and correcting them over time. It means respecting the people and cultures of First Nations – of any social or cultural group for that matter – and making room for them not only on the land, but also in our hearts.

Make connections

By Robert White

What does reconciliation mean to me? – Holding our brothers’ and sisters’ hands and making meaningful connections that can be passed on generationally.